On this page

19th century

- 1840s: Resident judges of the Port Phillip District

- 1850s: Establishment of the Supreme Court

- 1860s: New jurisdictions

- 1874-1884: New law courts

20th century

- 1901: Federation and the High Court of Australia

- 1917-1960s: The World Wars and post war

- 1960s-1990s: Social change

- 1995: Creation of the Court of Appeal

21st century

19th century

1840s: Resident judges of the Port Phillip District

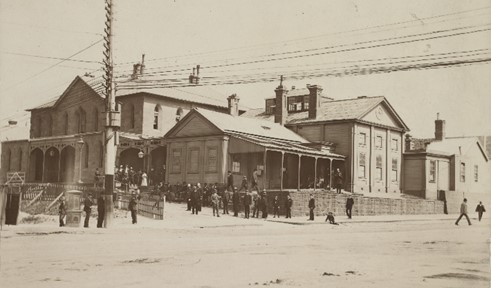

Judge John Walpole Willis arrived in the District of Port Phillip of New South Wales as the resident judge in March 1841. The Court sat for the first time on 12 April of that year in a vacated government store on the corner of King and Bourke Streets.

It heard significant criminal trials, including for capital punishment. Willis and his successors, Judges William Jeffcott and Roger Therry, also heard many commercial matters, including cases of insolvency, contract law and probate. In 1843, a purpose-built courthouse was erected on the corner of La Trobe and Russell Streets next to the new gaol.

1850s: Establishment of the Supreme Court

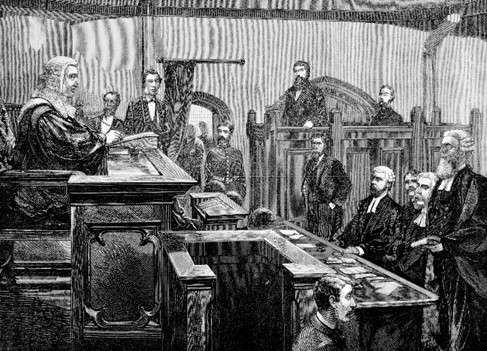

In 1851, the District of Port Phillip separated from New South Wales and the Colony of Victoria was established. One of the colony’s earliest legislative acts was to establish the Supreme Court with William a’Beckett becoming the first Chief Justice. He and the other judge appointed to the Court, Redmond Barry, took their seats on the Bench for the first time on 10 February 1852.

The discovery of gold in 1851 and the colony’s population growth led to a rapid increase in the business of the Court. A third judge, Justice Edward Eyre Williams, was appointed in 1852 and another, Justice Robert Molesworth, in 1854.

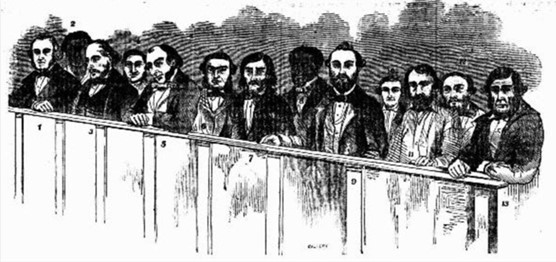

The most significant trials during this period were the treason trials of 13 of the men captured after the Eureka Stockade in 1854, all of whom were acquitted. The prosecutor in these trials, William Foster Stawell, later replaced William a’Beckett as Chief Justice in 1857.

1860s: New jurisdictions

During the 1850s and 1860s the gold rush caused an influx of people and wealth that led to large-scale building and infrastructure projects. The need to regulate and raise capital for this led to the first Company Law Acts in Victoria.

The Court also administered and adjudicated new social welfare laws that were introduced. The Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Act 1861 decreed that the Supreme Court would hear all divorce petitions. It retained this jurisdiction until the creation of the Family Court of Australia in 1975.

The Master in Equity was responsible for the guardianship of widows and orphans’ estates that were supervised by the Court. The Lunacy Statute 1867 expanded this function with the creation of the Master in Lunacy, a judicial officer who oversaw the property and legal affairs of those who had been incarcerated in asylums.

Still today, the Court continues to help care for some of the most vulnerable members of society through the administration of Funds in Court.

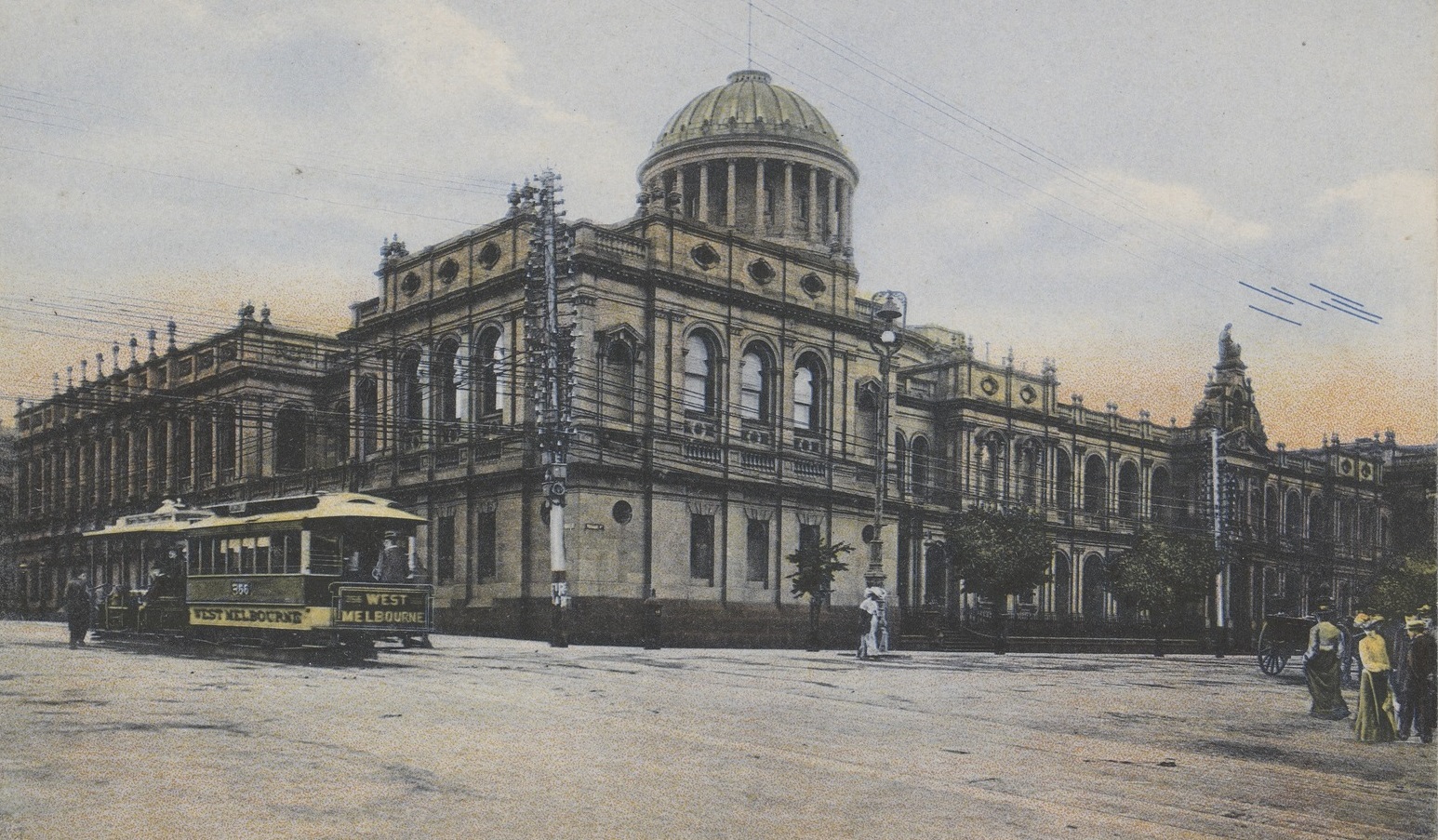

1874-1884: The new law courts

By the end of the 1850s, Melbourne’s growth had rendered the La Trobe Street courts inadequate. However, it was not until 1874 that work began on a new building at the corner of William and Lonsdale Streets. It was the largest and most expensive project in nineteenth century Australia, and marred by controversies, scandal, and budget blowouts.

The building opened in 1884 and was occupied by the Supreme and County Courts. By this time, the number of judges had increased to five, with a sixth judge appointed in 1886.

The most famous trial during this period, that of bushranger Ned Kelly, took place in 1880 in the La Trobe Street building – before the new courthouse was completed.

20th century

1901: Federation and the High Court of Australia

With Federation in 1901, Melbourne became the administrative capital of Australia. The High Court of Australia held its first sitting in 1903 in Banco Court and continued to hear cases in the Supreme Court until its own premises on Little Bourke Street were completed in 1928.

The new building was designed by John Smith Murdoch, the Commonwealth’s chief architect at the time, and represented an attempt to establish a more modern and dignified national style for Australian public buildings. It remained the home of the High Court for more than fifty years.

After the High Court moved to Canberra in 1980, the Federal Court occupied the building. In 1999, the Federal Court moved to a new location and the Supreme Court began to use the building to hear matters.

JOANNE BOYD:

Welcome to the High Court of Australia building.

It's a National Heritage listed building since 2007. It's ninety years old. It was built, as I said, between 1927, occupied 1928.

It's had three different sorts of courts here, the High Court, the Federal Court and since the turn of the century, it's been the Supreme Court of Victoria.

The High Court building is really a part of the court complex in the centre of Melbourne. So you've got the Trial building, which was built in 1884, the Court of Appeal building, which was built in 1894, and then this little building that was only built in the twentieth century in 1928.

JUSTICE MCMILLAN:

I'm Justice McMillan and I came to Bench in March 2012, and I sit in the Common Law Division, and I'm the head of the Trusts, Equity and Probate List and also the Testators Family Maintenance List.

I'm well aware that I'm in a building that's full of history and wonderful cases and wonderful people and it's really quite enthralling.

TIPSTAFF:

Silence. All stand please.

All persons having business before this Honourable Court are commanded to give their attendance and they shall be heard.

God save the Queen. Be seated, please.

1917-1960s: The World Wars and post war

The economic depression of the 1890s, compounded by World War I, led to a stagnation of Court business. This led to a reduction in the number of judges from six to four in 1917, which was not restored until 1919.

After the war, most of the men from the legal profession who had served resumed their careers at the Bar and as solicitors. An Act of Parliament passed in 1915, which reduced the requirements for the completion of articles for those who had served, enabled surviving law students to seek admission on their return to Australia.

Former premier of Victoria and attorney general of Australia, Sir William Irvine, was appointed Chief Justice in 1918 and remained in office until 1935. His successor, Sir Frederick Mann, the first Australian-born chief justice of Victoria, led the Court through most of World War II.

Lieutenant-General Edmund Herring was appointed Chief Justice in 1944. There was significant growth and change during his twenty-year stewardship, including the creation of the Chief Justice’s Law Reform Committee, which proposed law reform on non-political lines. He also oversaw the expansion of the Bench from six to 14 judges and the construction of new courtrooms to meet demand.

1960s-1990s: Social change

In 1964, Sir Henry Winneke was appointed Chief Justice. This marked the beginning of a period of much social change in Victoria:

- In 1965, Joan Rosanove – the first woman in Victoria to sign the Bar Roll – also became the first woman to be appointed Queen’s Counsel in Victoria after being repeatedly passed over since first applying 11 years earlier. This made her one of a few female Queen’s Counsel in Australia.

- It was not until 1964 that legislation was enacted to allow female citizens to be empanelled as part of juries in Victoria.

- The last capital punishment sentence was that of Ronald Ryan, who was executed in 1967 after much public debate and protest.

- In 1969, Justice Menhennit made a ruling in R v Davidson which allowed abortions under some circumstances in Victoria.

- The early 1990s saw the Court consumed with commercial matters following the corporate collapses of the late 1980s.

- In 1993, the Court appointed its first female judicial officer, with Kathryn Kings appointed a Master of the Supreme Court (today known as an Associate Justice).

- In 1996, Rosemary Balmford became the first woman to be appointed as a judge of the Court.

1995: Creation of the Court of Appeal

The Court of Appeal had its first ceremonial sitting on 8 June 1995 and started hearing cases on 13 June, following its establishment by the Victorian Parliament in late 1994. Victoria’s attorney general, Jan Wade, proposed that the new court would see Melbourne at the "forefront of the market of legal services".

Before this, a full court system was used where Supreme Court judges would sit as an appeal division. At the end of the 20th century, judges rotated between sitting on the full Bench or the appeal division. In the 19th century, they sat on appeals on their own judgments as there were only five judges, compared to more than 30 in 1995.

Victoria adopted a similar approach to the model used in Queensland, which meant that:

- The Court of Appeal would be part of the Supreme Court.

- The Chief Justice would remain the highest judicial officer of Victoria and also sit in the Court of Appeal.

- Eight judges and a president would be appointed to the Court of Appeal (view list of inaugural judges)

- The Court of Appeal sits in the former Crown Law Building located at 459 Lonsdale Street. There are currently 12 judges who hear cases from the Supreme Court Trial Division and County Court, and some from the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal.

21st Century

2000-2020: The new millennium

In 2003, one year after the Supreme Court marked its 150th anniversary, Justice Marilyn Warren was appointed Chief Justice – the first woman to hold this position in any court in Australia.

The first decade of the 21st century saw extensive renovation work to the interior of the Court buildings. The Court embraced digital technology with the adoption of electronic filing, digitally-enabled courtrooms and a stronger online presence. Litigation following the Black Saturday bushfires in 2009 was conducted in a specially designed eCourtroom and many of the more than 10,000 documents tendered in evidence were lodged electronically.

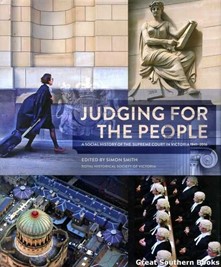

A special landmark publication celebrating the Court’s 175th anniversary was launched in 2016. Produced in collaboration with the Royal Historical Society of Victoria, the publication includes contributions from accomplished scholars, historians and members of the Victorian Bar, among others.

In 2017, the Court adopted new judicial robes, designed by the judges. Drawing in part on the judicial robes of the Supreme Court of Ireland, the style reflects strength and modernity, with hints of red kept as a tribute to the Court’s heritage.

That same year, Justice Anne Ferguson, a judge of appeal at the time, succeeded the Honourable Marilyn Warren AC as Chief Justice. Her Honour became the first judge with a background as a solicitor, rather than as a barrister, to be appointed to the role.

In 2019 the Court embarked on a project to rebuild outdated technological infrastructure, with all courtrooms and mediation rooms renewed to support the increasingly digital nature of matters heard.

Preparing for a day in court begins long before one steps into the courtroom, and with new technology they can now see the precise setup of the courtroom before stepping out.

As the judge sits to preside they use the tailored judges portal on their own secure judges network.

The Supreme Court of Victoria's digital transformation might be thought of as an iceberg, what lies beneath in the floors and walls holds the vast technological upgrades through new cabling, including fibre optics.

Peeking from the surface are Ultra HD monitors, surface studios on the bench, acoustic treatments and evidence display.

What was taken out is just as important as what has been put in.

Judicial officers have more flexibility in the different ways they work, and added capability to communicate with their associate to mute transcription and to view documents or evidence before broadcasting on their own monitor.

Technology in the upgraded spaces never distracts, nor blocks the focus of every courtroom - though standing before it.

The Associate is the hub of courtroom activity with the role increasingly connected and responsive.

In our digital courtroom, this includes raising documents and evidence for simple to complex witness interactivity, sending documents to the judge on private preview before presenting to the courtroom, as well as introducing video conferencing calls.

Each courtroom can now video conference on demand to anywhere in the world, to anyone with an internet connection, and device.

Remote, expert, and vulnerable witnesses may be dialled in by the court through the secure WebEx platform alleviating the need to attend a video conferencing centre.

All parties of the video conference call can see the courtroom, each other, and any documents being addressed and highlighted by others from their device.

Integrated court technology is suited to the witness before the court, purposefully built with straight-forward touchscreen capability that can be scaled up or down depending on the witness.

Each witness box is fitted with interactive evidence displays, where an eyewitness may use their finger to depict the movements they saw without any need for technological savvy.

That evidence can be broadcast on the Ultra High Definition monitors, while the Associate saves the file, so that it may be tended as evidence.

The ways that matters are litigated might potentially be transformed. Or they could very well be preserved with the advantage of augmented quality in evidence display.

Connectivity to Ultra High Definition monitors for Counsel is possible with any device, in any way, wirelessly and via HDMI cabling.

The Associate provides and revokes broadcasting access to the practitioners, wherever requisite throughout the matter.

2020s: The Court in a pandemic

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck in March 2020, it required a rapid and radical transformation to the way the Court operated. Hundreds of hearings went online, and by June 2020 most judicial officers and staff were operating off-site.

Throughout the pandemic the Court continually adjusted its ways of working to continue serving the Victorian community while operating in line with public health advice. The work of the Court continued with staff, judicial officers, the legal profession and Court users adapting to new ways of working both onsite and online.

In December 2020, nine months after the onset of the pandemic, the Court released a special ‘Court in a Pandemic’ episode of its award-winning podcast, Gertie’s Law, describing some of the changes during this period.

Listen to the episode of the Court’s award-winning podcast, Gertie’s Law, about how the Court responded to the challenge of a global pandemic.

Many efficiencies, technological improvements and new ways of working adopted during the pandemic will become part of the legal landscape into the future.